How to train your program verifier

- Author: Halley Young, Nikolaj Bjørner

What if you asked your favorite AI agent:

Produce mathematics at the level of Vladimir Voevodsky, Fields Medal-winning, foundation-shaking work but directed toward something the legendary Nikolaj Bjørner (co-creator of Z3) could actually use?

It was the start of our journey creating the a3 framework for generating Advanced Automated Analysis engines. We used the framework to create the a3-python verifier for Python. We chose Python because it is used widely by humans and LLMs, but is shunned by program verification tools due to its complexity.

For decades, researchers have developed verification tools while grappling with a fundamental challenge: scaling verification to mainstream languages. The difficulty stems both from the complexity of rich type systems and semantics, and from the need to continuously evolve verification tools in lockstep with rapidly changing language features. At the same time, LLM‑based code synthesis—while mind-numbingly effective—is not grounded in unambiguous semantics and cannot serve as a reliable source of truth. Yet the combination of (still mind-numbing) agent‑driven code synthesis and increasingly powerful verification infrastructure creates a new opportunity: to build tools that are grounded in formal methods and applicable in domains where no mortal would reasonably hand‑craft a verifier.

In the process of creating a3-python we used AI to (re)discover a foundation based on Hilbert’s Stellensatz theorems, integrate a top dozen advances in symbolic model checking, and import mathematical libraries for reasoning about PyTorch code. The a3-python system is now available for you to give a spin.

A3-python

Before we walk through the theory and pipeline, here is what a3 actually does on a real codebase.

We ran a3 scan on five core files from requests,

the most downloaded Python package on PyPI (183 functions, ~5000 lines):

$ pip install a3-python$ a3 scan requests/

STEP 5: BARRIER CERTIFICATE + DSE ANALYSIS Total bug instances: 183 Barrier results: Proven FP: 19/23 Remaining: 4 Barrier contributions: 9 post_condition 9 refinement_type 1 inductive_invariant

STEP 7: TRUE POSITIVE CANDIDATES TRUE POSITIVES (DSE-confirmed reachable): ⚠️ NULL_PTR in models.Response.__setstate__ ⚠️ NULL_PTR in sessions.Session.__setstate__ ⚠️ BOUNDS in utils.address_in_network ⚠️ BOUNDS in utils.select_proxy

SUMMARY Functions analysed: 183 Total bug instances: 183 Proven false positive: 179 (97.8%) Remaining candidates: 4 DSE-confirmed TPs: 4Of 183 potential bug instances, A3 proves 179 safe with formal barrier certificates. Four survive. All four are real:

-

address_in_network— BOUNDS. The function callsnet.split("/")and immediately indexes[1]:# requests/utils.py:670def address_in_network(ip, net):ipaddr = struct.unpack("=L", socket.inet_aton(ip))[0]netaddr, bits = net.split("/")# ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^# ValueError if net has no "/", BOUNDS if split returns 1 elementPass any

netstring without a/and this crashes. -

Response.__setstate__— NULL_PTR. Unpickling aResponseiteratesstate.items(), but nothing preventsstatefrom beingNone— a common issue with corrupted pickle files or version-mismatched serialization.

These are the kind of bugs that pass code review, pass tests, and then crash at 3 AM on malformed input.

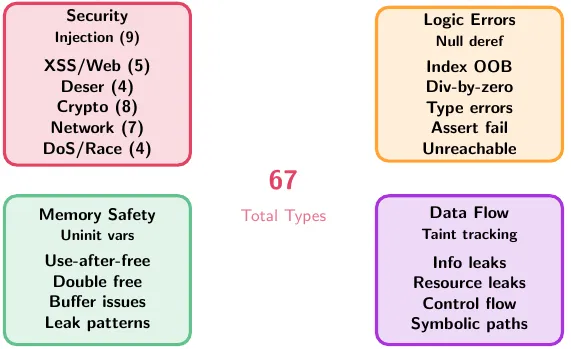

A3 is auto-generated and iterated: the analyzer was bootstrapped by asking AI to produce verification theory, then subjected to thousands of test iterations against real codebases. The theory was refined, the code was refined, and the surviving result is what ships. A3 identifies bugs across a set of pre-defined categories. If the code uses assertions it will attempt to establish that they hold on all code-paths, but general purpose verification is not the main use case for a3-python.

Querying for confluences

We did not start with let’s make a Python verifier. Instead our starting point was a prompt aimed at uncovering confluences between lines of thought that have been unlikely to be combined so far. Our prompt involving Voevodsky and the co-author of this blog is on purpose set up to trigger modern AI’s power to retrieve and extrapolate.

The earliest phase produced a long, ambitious manuscript on quantitative model checking. The central move was elegant:

- stop asking only “is the system safe?“

- start asking “how far is it from safety?“

- use that distance as a semantic object you can optimize.

In other words, make verification feel less like a courtroom verdict and more like geometry. The paper-level ideas were ambitious enough to be interesting and dangerous enough to be wrong in many ways once code entered the room. The approach was based on metric semantics: traces as distributions, properties as structured acceptance sets, distance to acceptance as a first-class quantity. Fascinating, but also provided instincts that survived the transition to working prototypes: Safety wasn’t considered purely a Boolean, 0/1, property. Uncertainty has shape. Quantitative semantics was used to prioritize work, and distance to satisfiability guided repair.

But put to the test, to solve real-world code bases, it was killing mountains of false positives and missed true bugs.

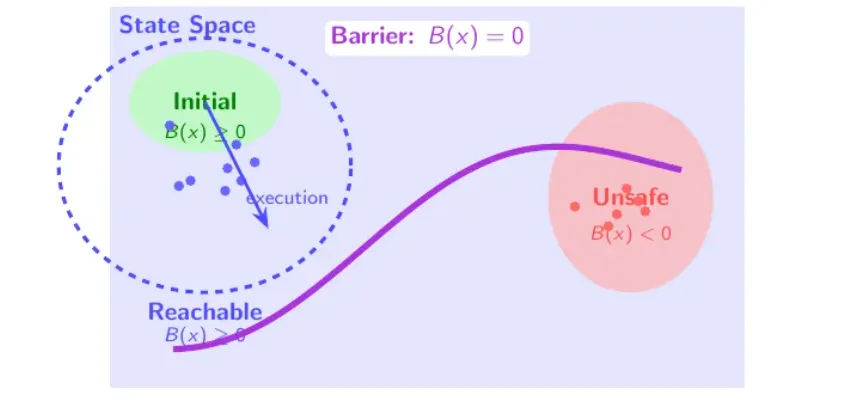

In a second iteration we queried our model to shift from measurement to separation. Instead of asking only how close is unsafe behavior?,

- what set is reachable,

- what set is unsafe,

- and can we synthesize a witness that keeps those sets disjoint?

It is much closer to mainstream symbolic program verification techniques. The objective in automated symbolic

program verification is to synthesize a barrier certificate B(s), where s are state variables of a program, so that

- initial states

sInitare on the safe side, they satisfyB(sInit) >= 0, - unsafe states are on the forbidden side, they satisfy

B(sBad) < 0, - and transitions never cross the fence, every non-negative

Bstate transitions to another non-negativeBstate.

The idea can be illustrated visually:

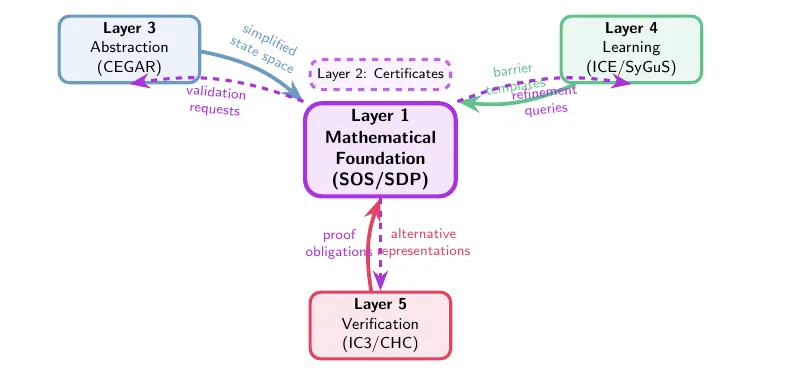

Our favorite LLM model (we used variants of GPT-5, Claude, noticing a phase shift in capabilities of Claude Opus by the end of October) determined that barriers should be expressed using polynomials over real and integer numbers. It introduced us to an algebraic proof machinery based on Hilbert’s Positivstellensatz, sums of squares, semi-definite programming, and the works. Considering that the z3 theorem prover supports both polynomial arithmetic but also domains that correspond directly to datatypes found in mainstream programming languages we were intrigued by the origins of this direction. While Claude appeared inclined to present results as its own inventions, we could send the 85 page document to copilot for a quiz on origins: The closest match was a method introduced 20 years ago for cyber physical systems and perhaps a thread of approaches used for synthesizing invariants from Farkas lemma.

From Foundational Math to Code

The eloquently-looking mathematical documents provide a great compass for agents to plan implementations. We still need an implementation plan. We asked GitHub Copilot CLI to synthesize a script to call Copilot in a loop, bootstrapping an implementation

Combine model-checker-plan with a desire to create a continuous copilot-cli workflow, by in a scheduled and structured way calling f”copilot -p ‘{prompt}’ —allow-all-tools”, with different prompts depending on where you are in the process. First flesh out the plan for the continual process, then write it as a .py using that call_copilot script. Note that unless told otherwise, copilot’s cli will create files itself, not return text of files. Note that part of the loop has to be downloading a large collection of python repos, and iteratively debugging for false negatives by having an LLM come up with a hard-to-spot bug of type n and having the model detect it, and debugging for all false positives by running the checker on all rut files in the entire set of repos, seeing where it finds a positive, and asking copilot-cli if it agrees that it’s a positive. Then it should iterate on its results, using barrier certificate theory where it can be helpful, and developing in other ways as well. The first part, though, should be developing a list of “moving parts” necessary, and iteratively building and then testing each moving part. Note that the implementation should be in python. This should consist of a .py python file which enacts this workflow. `

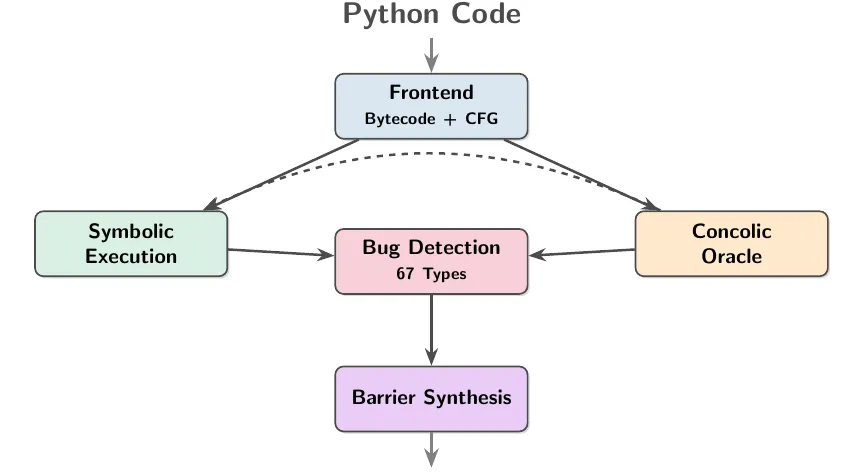

The agentic loop now focused on committing to execution details:

- bytecode-level control flow,

- normal and exceptional edges,

- frame/stack state,

- dynamic dispatch,

- unknown library behavior,

- and explicit unsafe predicates for real bug classes.

At a high-level the generated code implemented an architecture integrating symbolic execution and concolic oracles. More about oracles later.

Thus, a3-python was created automatically using copilot through a loop that comprised of five stages: (1) AI theorizing to identify cross-domain analogies, (2) coding, (3) testing based on synthetic suites and large repos, (4) code fixes and (5) patching the theoretical foundations, repeat from step (1).

The Computer Aided Verification kitchen sink

While a novel-looking foundation and an AI model’s ability to create end-to-end systems based on one approach has its own appeal, we deliberately abandoned theoretical purity for practical effectiveness. The kitchen sink pipeline throws every applicable proof strategy at each bug candidate, in order of cost:

For each unguarded bug candidate, A3 tries a cascade of barriers:

- EnhancedAssumeGuaranteeBarrier — Compositional reasoning about caller/callee contracts

- EnhancedPostConditionBarrier — Factory pattern and return-value analysis

- EnhancedRefinementTypeBarrier — Refinement type inference (e.g.,

len(x) > 0after a guard) - InductiveInvariantBarrier — Loop invariant synthesis via Z3

- ControlFlowBarrier — Dominator/post-dominator analysis on the CFG

- DataflowBarrier — Reaching definitions and value-range analysis

- DisjunctiveBarrier — Case-split reasoning for optional/nullable types

- UnanalyzedCalleeBarrier — Callee return-guarantee safety for unanalyzed functions

- ValidatedParamsBarrier — Parameter validation tag tracking

- DSEConfirmationBarrier — Z3-backed directed symbolic execution to construct concrete triggering inputs

When no barrier proves safety, DSE (directed symbolic execution) constructs a satisfying assignment — a concrete input that triggers the crash. This is the strongest evidence: not just “we couldn’t prove it safe,” but “here’s an input that breaks it.”

The concrete numbers on LLM2CLIP’s training code illustrate the cascade:

Total bug instances: 55 Barrier contributions: 4 post_condition (factory patterns, return guarantees) 4 refinement_type (parameter type narrowing) Proven FP: 8/14 Remaining: 6 DSE confirmed TP: 5Of 55 potential bugs, 41 are eliminated by guard detection alone (they sit behind if checks, try/except, or assertions).

Of the remaining 14, barrier certificates prove 8 more safe.

Of the remaining 6, DSE confirms 5 are reachable with concrete inputs — real bugs.

That is the kitchen sink point: treat great papers as interoperable components in a verification control loop, not as mutually exclusive camps.

The kitchen sink approach itself is prompted with a selection of highlights from the past 30 years of Computer Aided Verification. While our starting point was a specific technique honed in the theory of Positivstellensatz certificates, with accompanying toolsets and used for cyber physical systems we pivoted and asked copilot to examine relevant CAV literature, and it identified a smorgasbord of classics and wrote custom z3 verifiers in a3-python:

- Property-directed, CHC-style reachability engines and interpolation.

- Abstraction-refinement families (classic CEGAR, SAT predicate abstraction, lazy interpolation-based abstraction

- Learning/synthesis families (ICE, Houdini, SyGuS) that propose and refine invariants,

- Compositional assume-guarantee reasoning for interprocedural scaling

Concolic and Axiomatic Oracles

A big idea that makes dynamic symbolic execution workable with system calls or other function calls that are not practical to reason about symbolically is to just execute the code with concrete values. A dual idea is to axiomatize the effect of library calls and have symbolic execution use the axioms to pretend it executed the code of the library call. We asked copilot to specialize a3-python for both options. To axiomatize library calls, we used theories encoded in L∃∀Ns, MathLib4, and had copilot import them in a format that could be used by z3’s symbolic execution formalism.

Generic analysis on numeric libraries drowns in false positives — every tensor / x is a potential DIV_ZERO,

every tensor[i] a potential BOUNDS error. Real optimizers guard these operations with eps-clamped denominators,

shape assertions, and type dispatch. A3 encodes these patterns as library axioms — properties that PyTorch tensors

are known to satisfy — so the barrier certificates can reason about them.

Here is the result on PyTorch’s official Adafactor optimizer:

$ a3 scan pytorch_adafactor/

SUMMARY Functions analysed: 8 Total bug instances: 21 Proven false positive: 21 (100.0%) DSE-confirmed TPs: 021 potential bugs, every one proven safe. The barriers verify that PyTorch’s guards —

eps-clamped denominators, length assertions, careful initialization — prevent every candidate crash.

Now contrast this with Microsoft’s LLM2CLIP, which copies Adafactor from fairseq without PyTorch’s guards:

$ a3 scan llm2clip_training/

TRUE POSITIVES (DSE-confirmed reachable): ⚠️ DIV_ZERO in fp16.Adafactor._approx_sq_grad ⚠️ DIV_ZERO in fp16.Adafactor._rms ⚠️ BOUNDS in fp16.Adafactor.step ⚠️ DIV_ZERO in fp16.DynamicLossScaler._decrease_loss_scale ⚠️ BOUNDS in fp16.MemoryEfficientFP16Adam.step

SUMMARY Functions analysed: 47 Total bug instances: 55 Proven false positive: 49 (89.1%) DSE-confirmed TPs: 5The _approx_sq_grad bug is the most important finding:

# LLM2CLIP/training/fp16.py:748def _approx_sq_grad(self, exp_avg_sq_row, exp_avg_sq_col, output): r_factor = ( (exp_avg_sq_row / exp_avg_sq_row.mean(dim=-1).unsqueeze(-1)) # ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ .rsqrt_() .unsqueeze(-1) )When gradient values are all zero (dead neurons, masked parameters, early training with sparse gradients),

exp_avg_sq_row.mean() returns 0.0. The division produces Inf, and rsqrt_() propagates NaN — silently

corrupting the optimizer state for every subsequent training step with no error or warning.

This is a known bug class. HuggingFace Transformers

fixes it by initializing exp_avg_sq with fill_value=eps instead of zeros. LLM2CLIP’s copy never got that fix.

PyTorch’s version also guards it. A3 catches the unguarded copy; the barrier certificates formally confirm the guarded PyTorch version is safe.

Iterating for Quality — Results Across Real Codebases

The quality of a static analyzer is not best measured by what it finds. It is measured by what it does not report falsely. The noise level of static analyzers, and for that matter fuzz testers, have a long and tortured history of irritating developers with bug reports that don’t matter. Here is a summary of A3 results across four well-known open-source projects:

| Codebase | Functions | Bug instances | Proven FP | Candidates | DSE-confirmed TPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PyTorch Adafactor | 8 | 21 | 21 (100%) | 0 | 0 |

| requests (core) | 183 | 183 | 179 (97.8%) | 4 | 4 |

| DeepSpeed (utils) | 83 | 77 | 74 (96.1%) | 3 | 3 |

| LLM2CLIP (training) | 47 | 55 | 49 (89.1%) | 6 | 5 |

Every TP (true positive) finding across these four codebases is a real, exploitable bug — not a style complaint or a theoretical concern. The highlights:

-

DeepSpeed

_ensure_divisibility(DIV_ZERO) — A function whose entire purpose is to validate that numerator is divisible by denominator crashes on its own unvalidated input. Whendenominator=0, Python’s%operator raisesZeroDivisionErrorbefore theassertcan produce its helpful error message:# deepspeed/utils/groups.py:64def _ensure_divisibility(numerator, denominator):"""Ensure that numerator is divisible by the denominator."""assert numerator % denominator == 0 # ZeroDivisionError before assertThis is called with user-configurable values like

expert_parallel_sizeandtensor_parallel_size. -

DeepSpeed

SynchronizedWallClockTimer.__call__(BOUNDS) — The innerTimerconstructor and event-timer list can be accessed on empty sequences viaelapsed_recordsorevent_timersin the innerTimerclass. -

DeepSpeed

ThroughputTimer._is_report_boundary(DIV_ZERO) —self.global_step_count % self.steps_per_outputwheresteps_per_outputcan be zero. TheNonecheck guards againstNonebut not against0. -

requests

address_in_network(BOUNDS) — Destructuringnet.split("/")into two variables without checking the split produced two segments. -

requests

Response.__setstate__(NULL_PTR) — Iteratingstate.items()during unpickling without aNonecheck onstate. -

LLM2CLIP

_approx_sq_grad(DIV_ZERO) — Silent NaN corruption from dividing by a zero-valued mean (detailed above).

Symbolic-Neural

A3’s architecture occupies a specific quadrant: symbolic verifier + neural triage.

- The symbolic engine is deterministic, auditable, and runs without GPU compute or API keys.

- The neural component (agentic LLM) handles only the uncertain residue — the 1-4% of candidates where formal proof and disproof both stop.

This makes the tool eco-friendly (no LLM calls for 96%+ of findings), explainable (barrier certificates provide proof artifacts), and deployable in CI without rate limits or API costs for the vast majority of analysis.

When discussing the a3 project with colleagues, the first question that comes to mind is often how do you trust the verifier? Indeed, we observed how the model under Copilot CLI could barter and cheat, producing just enough code to pass unit tests, but not enough to be resilient. Our prototype undeniably contains shortcuts that would not pass a quality code review. But, we have harnessed a3-python by taking the approach of translation validation: verify the output of the verifier; and fighting AI slop with AI slop: aggressively generate code, then subject everything to adversarial testing.

It fights slop at three levels:

-

Theoretical slop AI-generated theory is forced through explicit semantics and proof obligations.

-

Implementation slop Analyzer claims are checked against tests, concrete runs, and refinement loops.

-

Operational slop Alert floods are collapsed by static filters before LLM triage and human review.

So yes, this is AI slop vs AI slop, but not symmetrically.

- Upstream AI expands hypothesis space.

- Midstream formal/static machinery prunes it brutally.

- Downstream agentic AI handles the hard residue.

That asymmetry is what makes it useful.

The ease to mix and match programming languages, symbolic backends, to import axioms, and integrate neural verdicts, suggests a new era for program verification: create custom verification engines that target domain specific needs, whether specific languages or integration with libraries. So far we extracted prototypes static verifiers for Python and Rust. They were created as offsprings of a factory prompt that facilitates specialization to all mainstream programming languages. A practical difficulty with maintaining large systems that invoke proprietary protocols is that developers who understand coding may be disjoint from subject matter experts in library behavior and disjoint from architects. The potential for a3 goes beyond finding common classes of Python coding errors, but to bring deep understanding of intent to static verification.